From Playgrounds to Screens: Navigating Mental Health in the Digital Age

“The smartphone is the modern-day hypodermic needle, delivering digital dopamine 24/7 for a wired generation.” ― Anna Lembke, Dopamine Nation: Finding Balance in the Age of Indulgence

Jonathan Haidt references Anna Lembke in his book, The Anxious Generation, which I recently read. Released in March 2024, the book reveals a multitude of research studies supporting what we, as educators, have witnessed over the last 15 years in the classroom: decreased motivation and attention span, and unhappy, depressed students.

Our reliance on and addiction to devices—phones, tablets, laptops—extends beyond the classroom. I've known the addiction was bad, but Haidt paints a bleak picture of the future, highlighting various mental health and other concerns. However, he also offers potential solutions if everyone takes steps to address the issues. Links to Haidt’s research and studies can be found at The Anxious Generation Book website.

Here are my THREE main takeaways from the book:

Brain and Social Development

Our students’ brains are not fully developed, particularly the prefrontal cortex. This part of the brain is responsible for executive functions, including attention, reasoning, judgment, problem-solving, creativity, emotional regulation, impulse control, and awareness of one’s own and others' functioning (Scott and Schoenberg, 2011).

Haidt focuses on teens in general, but a significant increase in mental health issues is plaguing those Mark McCrindle calls Gen Alpha. Born between 2010 and 2024, Gen Alpha experiences reduced face-to-face interaction in the real world and spends more time in the virtual world. This additional time online has led to increased depression and suicide, especially among girls. This international mental health crisis is discussed by Zach Rausch on Haidt’s blog, Under Babel, where Rausch cites numerous studies showing the alarming trend.

Overprotection in the “Real” World vs. Under-protection in the Digital World

The term “helicopter parent” has existed since the late 1960s, but it became more common in the mid-1990s. Several cultural changes led to increased overprotection of children during this period.

In her book How to Raise an Adult, Julie Lythcott-Haims identifies four main reasons for this increased protection: abduction fears, increased homework, lack of play influenced by the report A Nation at Risk, the self-esteem movement, and the creation of the playdate (Lythcott-Haims, 2015).

This overprotection in the real world led to underprotection in the virtual world. By shielding our children from physical dangers, parents inadvertently exposed them to online video games (mostly boys), social media influencers, and online predators. Social media platforms prey on young girls, exacerbating social comparison and increasing feelings of loneliness and depression despite the appearance of connectedness.

Haidt’s Recommendations for Better Mental Health

- No smartphones before high school: Give children basic phones without internet until about age 14.

- No social media before age 16.

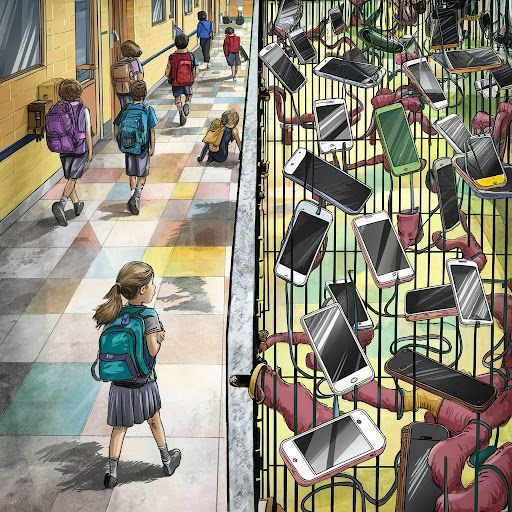

- Phone-free schools: Keep schools free from smartphones to encourage focus and social interaction.

- More unsupervised play and independence: Allow children more freedom to play and explore on their own to help them develop social skills and overcome anxiety.

Conclusion

Research conclusively shows that cellphone and social media addiction are real. While I appreciate Haidt’s suggested solutions, we need to be realistic in our problem-solving. After reading the book, I have more questions than answers.

I'll leave you with these questions to ponder:

- How many of us, as adults, can or are willing to reduce our screen time?

- Can we, as adults, tell our children they can't be on their devices while we are actively on ours?

- Are schools willing to push and enforce no cell phone zones, and more importantly, model it for students?

- Are parents willing to support administrators and teachers that enforce no cell phone use in schools?

- Can or will companies, specifically social media companies, “increase security” so those under the required ages are unable to access?

- How can children reduce their time or change their behavior when “connectedness” is all that they know?

Sources:

Lythcott- Haims, Julie. How to Raise and Adult. Henry Holt and Co, 2015.

Rausch, Zach, and Jon Haidt. “Suicide Rates Are up for Gen z across the Anglosphere, Especially for Girls.” Suicide Rates Are up for Gen Z across the Anglosphere, Especially for Girls, After Babel, 30 Oct. 2023, www.afterbabel.com/p/anglo-teen-suicide.

Scott, James G, and Mike R Schoenberg. “Frontal Lobe/Executive Functioning.”

Chapter 10 Frontal Lobe/Executive Functioning, Einstein Med, 2011,

einsteinmed.edu/uploadedFiles/departments/neurology/Divisions/Child_Neurology/Child_Neurology_References/Executive_Fnc/Frontal%20Lobe.EF.pdf.

Notes:

Images were created utilizing the website Ideogram.ai, a text to image AI tool

ChatGPT 3.5 was used to organize and improve the wording of my original thoughts

ChatGPT 3.5 created the title of this post

Jeremy is a TEDx Speaker and a Jr. High Computers & STEM Teacher in Effingham, IL as well as a Governing Board member for IDEA. He has earned a Masters in Educational Policy from the University of Illinois and a Masters in Teaching from Greenville University. His goal is to inspire students, teachers and anyone he comes into contact with to be a lifelong learner. Jeremy believes education is the key to solving our world’s problems. In his free time, Jeremy enjoys traveling,writing, spending time in coffee shops, and spending time with his family watching old TV shows on Netflix.